A RealNVP conditional normalising flow (from scratch?)

Published:

In this post I will attempt to give an introduction to conditional normalising flows, not to be confused with continuous normalising flows, that model both \(\vec{\theta}\) and \(\vec{x}\) in the conditional distribution \(p(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x})\). I was nicely surprised at how simple it is to implement compared to unconditional normalising flows, so I thought I’d show this in a straightforward way. Assumes you’ve read my post on Building a normalising flow from scratch using PyTorch.

Resources

- Masked Autoregressive Flow for Density Estimation

- Specifically section 3.7

- This is literally a single paragraph but it just expressed the concept so simply that when I read it a lot of things slotted into place in my head.

- Learning Likelihooods with Conditional Normalising Flows

- Specifically section 3.1

- Recent Advances in Simulation-based Inference for Gravitational Wave Data Analysis

- The general discussion and what they did have for NPE (effectively conditional flows) was really helpful when figuring out how to structure this

- Also from what I’ve read of the references they are also of similar quality

- Neural posterior estimation for exoplanetary atmospheric retrieval

- Not sure why but the explanations in this also just happened to click a few things into place

Table of Contents

Motivation

If you’ve clicked on this blog post you’re likely already interested in conditional flows and/or conditional density estimation but just for the non-believers out there, I’ll still lay out the use cases for conditional flows.

The essence of the method is that instead of just learning the probability distribution for a set of parameters \(p(\vec{\theta})\) you can learn the conditional probability distribution \(p(\vec{\theta}|\vec{x})\) which allows you to do many things including but not limited to:

- Pre-train a conditional density based on possible realisations of the data and when you want to apply it in real life, it’s just a question of plugging the data in. If you get more data, you can then just plug that in, practically without having to redo the analysis. i.e. Amortised Inference

- e.g. Dingo is a gravitational wave analysis tool that in part utilises it for this purpose

- Predict future states based on past states, i.e. forecasting

- If my state was \(x_i\) what is the probability that the state \(x_{i+1}\) will be…

- Conditional generation of data/parameters/variables

- e.g. generating high resolution images from low resolution ones. For example SRFlow: Learning the Super-Resolution Space with Normalizing Flow

- e.g. approximating an expensive generator

Otherwise, I’ll try and keep this short and just move on to how they work.

Mathematical Setup

If you have read my other post on Building a normalising flow from scratch using PyTorch, or are already familiar with how RealNVP architectures/normalising flows are constructed, then a conditional flow is really not that much more complicated.

The idea behinds normalising flows is that they transform some base distribution variable \(\vec{u}\), following some simple analytical distribution \(p_\vec{u}\), into the density that we wish to investigate \(p_\vec{\theta}(\vec{\theta})\),

\[\begin{align} p_\mathbf{\vec{\theta}}(\vec{\theta}) &= p_\vec{u}(\vec{u}) \vert J_T(\vec{u})\vert^{-1} \\ &= p_\vec{u}(T^{-1}(\vec{\theta})) \vert J_{T^{-1}}(\vec{\theta}) \vert . \end{align}\]For RealNVP, the transformation is an affine coupling block structure (with \(s\) and \(t\) neural networks) for intermediary variable \(\vec{z}^i\). With \(i\) referring to the \(i^{\textrm{th}}\) layer, with \(\vec{z}^0 = \vec{u}\) and for N layers, \(\vec{z}^N = \vec{\theta}\).

\[\begin{align} z^{i}_{1:d} &= z^{i-1}_{1:d} \\ z^{i}_{d+1:D} &= z^{i-1}_{d+1:D} \odot \exp(s(z^{i-1}_{1:d})) + t(z^{i-1}_{1:d}). \end{align}\]This means that the jacobian for the \(i^{\textrm{th}}\) layer of transformations \({T_i}\) (and subsequently the total jacobian) doesn’t require any derivatives of the \(s\) and \(t\) and looks like the following,

\[\begin{align} J_{T_i} &= \left[ \begin{matrix} \mathbb{I}_d & \vec{\mathbf{0}} \\ \frac{\partial z^{i}_{d+1:D}}{\partial z^{i-1}_{1:d}} & \textrm{diag} \left(\exp\left[ s(z^{i-1}_{1:d}) \right] \right)\\ \end{matrix} \right]. \end{align}\]The bulk of this does not change a lick, except that we need to put the dependence on \(\vec{x}\) somewhere. No deep abstraction here, we just need to put \(\vec{x}\) somewhere where the neural networks can learn how to transform \(\vec{u}\) to \(\vec{\theta}\) using information on \(\vec{x}\).

Because of the construction of RealNVP (and flows in general) we can make the neural networks involved as complicated as we like (pretty much), as the setup doesn’t require derivatives over them. Hence, the easiest thing to do, and what is commonly done, is to just include \(\vec{x}\) into the inputs of the neural networks,

\[\begin{align} z^{i}_{1:d} &= z^{i-1}_{1:d} \\ z^{i}_{d+1:D} &= z^{i-1}_{d+1:D} \odot \exp(s(z^{i-1}_{1:d}, \vec{x})) + t(z^{i-1}_{1:d}, \vec{x}). \end{align}\]And that’s it. Some setups such as that in Masked Autoregressive Flow for Density Estimation also include a couple extra neural networks that directly manipulate the base distribution for example with a base distribution,

\[\begin{align} p_\vec{u}(\vec{u} | \vec{x}) = \mathcal{N}(\vec{u} \vert \mu(\vec{x}), \sigma^2(\vec{x})), \end{align}\]with \(\mu\) and \(\sigma^2\) being learned by neural networks. For this post I think it will be simpler to implement just through the transformations, that would be able to handle the subsequent shifts and dilations anyway, but in real world circumstances may lead to more unstable training.

Practical Implementation: One-shot conditional

The first thing that we want to do is create a dedicated class for embedding the conditional variables. This allows us to have a bit of flexibility later on regarding applications in variational inference, but additionally, allows something within the work to independently learn important features of the data. AND on top of that if you have a large number of these conditional variables that’s comparatively larger than the number of variables you are actually constructing the probability density over, this means the inputs to the networks transforming the samples won’t be overpowered by the number of conditional variables.

Overall, it makes the training easier, which is much harder when compared to unconditional flows.

For the embedding, we won’t do anything fancy, we’ll just make a PyTorch compatible module by inheriting from the nn.Module, specify the dimensionality of our input (number of conditional variables), how large we want our hidden layers to be, and how large we want the output or what will be the inputs to the neural networks representing the conditional variables.

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class ConditionEmbedding(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim=2, embedding_size=4, embed_hidden_dim=64):

super().__init__()

self.point_net = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(input_dim, embed_hidden_dim), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(embed_hidden_dim, embed_hidden_dim), nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(embed_hidden_dim, embedding_size), nn.ReLU())

def forward(self, x):

per_point = self.point_net(x)

return per_point

Let’s test that out, just to see that it can take in some example inputs. Let’s say we wanted to approximate our distributions with 100 samples from our conditioned probability distribution \(p(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x})\) with \(\vec{x}\) being 3D with 64 nodes in our hidden layers. That would look something like,

x = torch.randn(100, 3)

cond_net = ConditionEmbedding(input_dim=3, embedding_size=4, embed_hidden_dim=64)

embedding = cond_net(x) # shape: (64,)

print(embedding.shape)

torch.Size([100, 4])

And similar to my previous post, starting with the overarching RealNVP class, we need the same information as before, plus that needed to intialise our embedding neural network.

class RealNVPFlow(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, num_dim, num_flow_layers, hidden_size, cond_dim, embedding_size):

super(RealNVPFlow, self).__init__()

self.dim = num_dim

self.num_flow_layers = num_flow_layers

self.embedding_size = embedding_size

# setup conditional variable embedding

self.cond_net = ConditionEmbedding(

input_dim=cond_dim,

embedding_size=embedding_size,

embed_hidden_dim=hidden_size)

We then initialise a base distribution, which I’ll pick to be an uncorrelated 2D normal again.

# setup base distribution

self.distribution = dist.MultivariateNormal(torch.zeros(self.dim), torch.eye(self.dim))

I’ll then re-use the code from my previous post to set up the conditional blocks.

# Setup block masks

# size of little d as in Density estimation using Real NVP - https://arxiv.org/abs/1605.08803

self.little_d = self.dim // 2

# size of the remaining block

self.big_d = self.dim - self.little_d

self.mask1_to_d = torch.concat((torch.ones(self.little_d), torch.zeros(self.big_d)))

self.mask_dp1_to_D = torch.concat((torch.zeros(self.little_d), torch.ones(self.big_d)))

tuple_block_masks_list = [

(self.mask1_to_d, self.mask_dp1_to_D) for dummy_i in range(self.num_flow_layers//2)

]

block_masks_list = []

for mask1, mask2 in tuple_block_masks_list:

block_masks_list.append(mask1)

block_masks_list.append(mask2)

if self.num_flow_layers%2:

block_masks_list.append(self.mask1_to_d)

block_masks = torch.vstack(block_masks_list)

# we aren't training the block nature of the model, so we don't need to train it --> requires_grad=False

self.block_masks = nn.ParameterList([

nn.Parameter(torch.Tensor(block_mask), requires_grad=False) for block_mask in block_masks

])

And then finally, we’ll set up the transformation layers almost exactly as before, but they will now need to know the size of the output of our embedding network. As they will also be taking that as inputs now.

self.hidden_size = hidden_size

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

RealNVP_transform_layer(

block_mask,

self.hidden_size,

embedding_size=embedding_size) for block_mask in self.block_masks])

And then the rest of the class is also exactly the same except we need to put the conditional parameters through the embedding network or put the outputs of the network into the transformation layers.

def log_probability(self, y, cond_x):

# Putting the conditional parameters through the embedding network

cond_emb = self.cond_net(cond_x)

if len(y)!=len(cond_emb):

# In case the inputs presume a distribution of y for a single set of cond_x

cond_emb = cond_emb.repeat(len(y), 1)

log_prob = torch.zeros(y.shape[0])

for layer in reversed(self.layers):

# passing cond_emb through the transformation layers

y, inv_log_det_jac = layer.inverse(y, cond_emb=cond_emb)

log_prob += inv_log_det_jac

y = torch.where(torch.isnan(y), -1000, y)

log_prob += self.distribution.log_prob(y)

return log_prob

def rsample(self, num_samples, cond_x):

y = self.distribution.sample((num_samples,))

return self.transform(y, cond_x)

def transform(self, y, cond_x):

if len(y)!=len(cond_x):

# Again, in case the inputs presume a distribution of y for a single set of cond_x

cond_x = cond_x.repeat(len(y), len(cond_x))

# Putting the conditional parameters through the embedding network

cond_emb = self.cond_net(cond_x)

for layer in self.layers:

# passing cond_emb through the transformation layers

y, log_det = layer.forward(y, cond_emb=cond_emb)

return y

Now similarly the transformation layers barely change, just remembering that they additionally take the outputs of the embedding network as extra inputs.

from torch import nn

class RealNVP_transform_layer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, block_mask, hidden_size, embedding_size):

super(RealNVP_transform_layer, self).__init__()

self.dim = len(block_mask)

self.embedding_size = embedding_size

# requires_grad=False coz we ain't training the block nature of the flow

self.block_mask = nn.Parameter(block_mask, requires_grad=False)

# Same neural network setup except the input needs to be larger to accomodate the embedding outputs

self.sequential_scale_nn = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(in_features=self.dim + self.embedding_size, out_features=hidden_size), nn.LeakyReLU(),

nn.Linear(in_features=hidden_size, out_features=hidden_size), nn.LeakyReLU(),

nn.Linear(in_features=hidden_size, out_features=self.dim))

# Same neural network setup except the input needs to be larger to accomodate the embedding outputs

self.sequential_shift_nn = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(in_features=self.dim + self.embedding_size, out_features=hidden_size), nn.LeakyReLU(),

nn.Linear(in_features=hidden_size, out_features=hidden_size), nn.LeakyReLU(),

nn.Linear(in_features=hidden_size, out_features=self.dim))

def forward(self, z, cond_emb):

z_block_mask = z*self.block_mask

# the cond_emb are just extra inputs

nn_input = torch.cat([z_block_mask, cond_emb], dim=-1)

scaling = self.sequential_scale_nn(nn_input)

shifting = self.sequential_shift_nn(nn_input)

y = z_block_mask + (1 - self.block_mask) * (z*torch.exp(scaling) + shifting)

log_det_jac = ((1 - self.block_mask) * scaling).sum(dim=-1)

return y, log_det_jac

def inverse(self, y, cond_emb):

y_block_mask = y * self.block_mask

# the cond_emb are just extra inputs

nn_input = torch.cat([y_block_mask, cond_emb], dim=-1)

scaling = self.sequential_scale_nn(nn_input)

shifting = self.sequential_shift_nn(nn_input)

z = y_block_mask + (1-self.block_mask)*(y - shifting)*torch.exp(-scaling)

inv_log_det_jac = ((1 - self.block_mask) * -scaling).sum(dim=-1)

return z, inv_log_det_jac

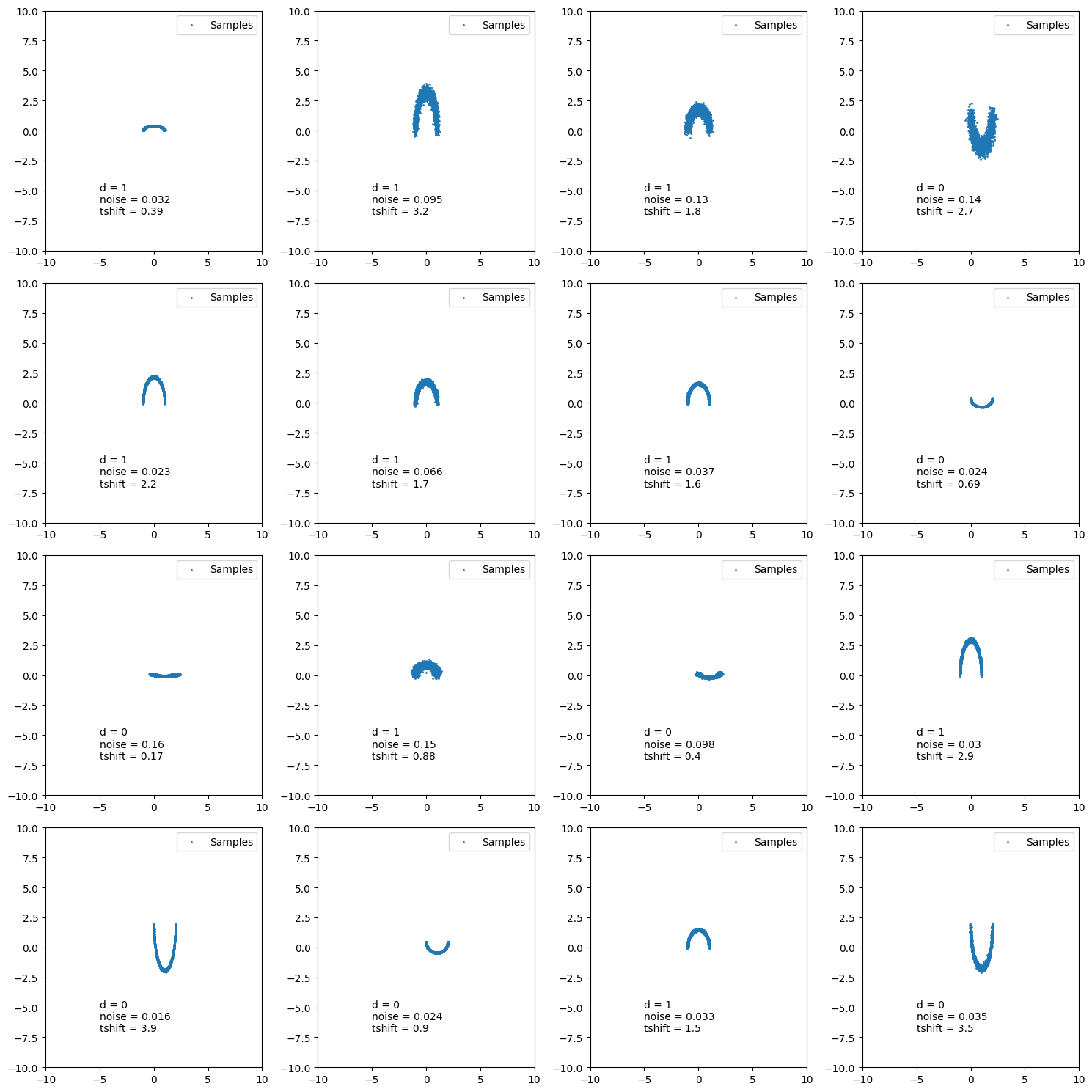

Example Training: One-shot conditional with double moon distribution

Now let’s assume that the conditional distribution that we are trying to approximate is a double moon distribution with free parameters:

- \(d\) :- whether the samples come from the upper moon or lower moon

- \(\text{noise}\) :- gaussian noise parameter on double moon samples

- \(t_{dil}\) :- vertical dilation parameter

Putting this into code looks like the following.

from torch import nn

import numpy as np

from sklearn.datasets import make_moons

sample_noise_dist = dist.Normal(0., 1.)

class LikelihoodForCond(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(LikelihoodForCond, self).__init__()

self.base_dist = dist.Normal

def rsample(self, cond, n_samples=None):

if cond.dim()==1:

cond = cond.unsqueeze(0)

d, noise, tshift = cond.T

if n_samples is None:

n_samples = len(d)

if len(d)!=n_samples:

cond = cond.repeat((n_samples, 1))

# print(cond.shape)

d, noise, tshift = cond.T

repeated_d = d.repeat((2, 1)).T

samples = np.empty((n_samples, 2))

samples = np.where(

repeated_d==np.array([1, 1]),

make_moons(n_samples=(n_samples, 0))[0],

samples)

samples = np.where(

repeated_d==np.array([0, 0]),

make_moons(n_samples=(0, n_samples))[0],

samples)

samples = torch.tensor(samples) \

+ noise[:, None]*torch.vstack(

(

self.base_dist.sample((n_samples,)),

self.base_dist.sample((n_samples,))

)).T

samples[:, 1] = samples[:, 1]*tshift

return samples

Let’s see how this looks.

ln_like = LikelihoodForCond()

fig, axes = plt.subplots(4, 4, figsize=(15, 15))

axes = np.array(axes).flatten()

for ax in axes:

_example_cond = sample_conditionals(n_samples=1).squeeze()

example_theta_samples = ln_like.rsample(_example_cond, n_samples=2000)

ax.scatter(*example_theta_samples.T, s=1, label="Samples")

ax.set(

xlim=[-10, 10],

ylim=[-10, 10],

)

ax.text(

-5, -5, f"d = {float(_example_cond[0]):.2g}"

)

ax.text(

-5, -6, f"tshift = {float(_example_cond[1]):.2g}"

)

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

The training is then exactly the same as the previous post, except we need to feed in the conditional samples.

Mathematically this looks like minimising the divergence with respect to the parameters of our approximation \(\vec{\varphi}\),

\[\begin{align} \text{KL}[p\vert\vert q] = \mathbb{E}_{\vec{\theta}\sim p(\vec{\theta}\vert \vec{x})} \left[\log p(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x}) - \log q(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x} ; \vec{\varphi}) \right]. \end{align}\]This however doesn’t take into account how we generated our samples from \(\vec{x}\). All we need to do for that is average over them.

\[\begin{align} L^{\text{new!}}(\vec{\varphi}) = \mathbb{E}_{\vec{x}} \left[ L(\vec{\varphi}) \right] = \mathbb{E}_{\vec{x}\sim p(\vec{x})} \left[ \mathbb{E}_{\vec{\theta}\sim p(\vec{\theta}\vert \vec{x})} \left[\log p(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x}) - \log q(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x} ; \vec{\varphi}) \right]\right] \end{align}\]Or perhaps more simply.

\[\begin{align} L^{\text{new}\,\text{new}}(\vec{\varphi}) = L^*(\vec{\varphi}) = - \mathbb{E}_{\vec{x}, \vec{\theta} \sim p(\vec{x}, \vec{\theta})} \left[\log q(\vec{\theta}\vert\vec{x} ; \vec{\varphi}) \right] \end{align}\]Now the only question is how do we implement this in practice? Well it’s almost exactly the same as before once we have our data, just that we need to separate our parameters of interest \(\vec{\theta}\) and our conditional parameters \(\vec{x}\), and feed them in!

import tqdm

import numpy as np

from copy import deepcopy

from torch.utils.data import TensorDataset, DataLoader

def train(model, data, epochs = 100, batch_size = 256, lr=1e-3, prev_loss = None):

train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(data, batch_size=batch_size)

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=lr)

if prev_loss is None:

losses = []

else:

losses = deepcopy(prev_loss)

with tqdm.tqdm(range(epochs), unit=' Epoch') as tqdm_bar:

epoch_loss = 0

for epoch in tqdm_bar:

for batch_index, training_data_batch in enumerate(train_loader):

# Extracting samples

theta = training_data_batch[:, :2] # density dist variables

cond_samples = training_data_batch[:, 2:] # conditional variables

# Evaluating loss

log_prob = model.log_probability(theta, cond_samples)

loss = - log_prob.mean(0)

# Neural network backpropagation stuff

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

epoch_loss += loss

epoch_loss /= len(train_loader)

losses.append(np.copy(epoch_loss.detach().numpy()))

tqdm_bar.set_postfix(loss=epoch_loss.detach().numpy())

return model, losses

We’ll then initialise our model with 8 flow layers and 16 nodes in the hidden layers.

torch.manual_seed(2)

np.random.seed(0)

num_flow_layers = 8

hidden_size = 16

data_to_train_with = torch.vstack((training_theta_samples.T, training_conditional_samples.T)).T

NVP_model = RealNVPFlow(num_dim=2, num_flow_layers=num_flow_layers, hidden_size=hidden_size, cond_dim=3, embedding_size=4)

trained_nvp_model, loss = train(NVP_model, data_to_train_with, epochs = 500, lr=1e-3)

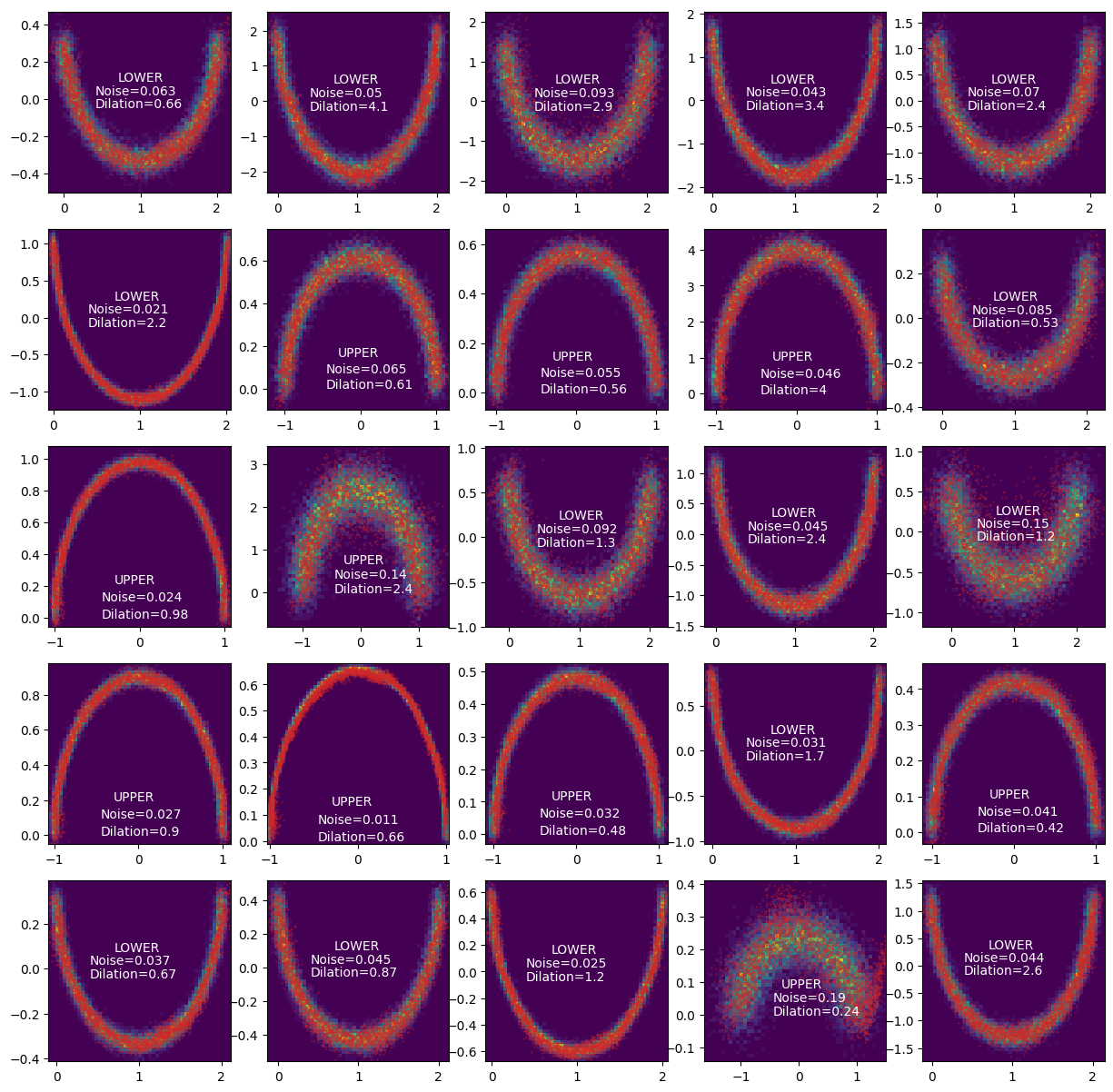

With this and some additional training, we can get the following. The red dots represent the approximated distribution and the density in the back use the relevant exact sample distribution.

Woo!

Conclusion

Now this is fantastic (if I do say so myself) but isn’t that useful in the general case of data analysis, where our conditional variables are data. In which case we can’t just sample them willy-nilly as above as the inherent order of dependecies is switched. This would be fine with a couple modifications to approximate a single observation like this, which is quite useful in the case that it is intractable. However, doing all this for the case of a posterior for an entire set of data requires a little more work that I’ll instead put into a post on Simulation-Based Inference which is the realm that this is in.