An introduction to continuous normalising flows

Published:

In this post I will attempt to give an introduction to continuous normalising flows, an evolution of normalising flows that translate the idea of training a discrete set of transformations to approximate a posterior, into training an ODE or vector field to do the same thing.

Resources

As usual, here are some of the resources I’m using as references for this post. Feel free to explore them directly if you want more information or if my explanations don’t quite click for you:

- Neural Ordinary Differential Equations

- Original paper that introduced the underpinning theory for continuous normalising flows and subsequently flow matching

- I broadly follow the paper skipping some bits on the utility on the application of just the neural ODEs instead of neural networks

- torchdiffeq cnf example

- The construction of the continuous normalising flow in this example is basically the same as my own example. As every time I made my own example this one was just better and simpler. Thanks Dr Chen

- Wikipedia’s Residual Neural Network page

- For a quick ref if you’re unfamiliar

- Vai Patel’s post on Deriving the Adjoint Equation for Neural ODEs using Lagrange Multipliers

- I honestly didn’t really get how the adjoint method came about before writing this post and reading this for reference. I actually recommend you read this later on, so maybe just open it now?

- My other posts on normalising flows, just because I reference them a couple times for examples or basic theory.

- Wikpedia’s page on Jacobi’s formula

- The proof within I reproduce in the appendix for my post for completeness, and so that I actually write it down and hopefully not forget it

Table of Contents

- Motivation

- Core Idea

- ‘Ground Up’ Continuous Normalising Flow

- Training our CNF

- Proof of the determinant-jacobian trace-derivative formula

- The Adjoint Method

- Conclusion

Motivation

Normalising flows as discussed in my other posts (intro and making one from scratch) tout how wonderful normalising flows are. They have the ability to not only efficiently explore high dimensional distributions, and sample them all, but also create a functional representation for them. However, if you want to model a really complex distribution with many modes and non-gaussian behaviour you may want a more complex transformation behind your normalising flow. However, the calculation can be quite arduous because of the need to calculate the determinant of the transformations’ jacobian. Or maybe you want to nicer way to train a conditional normalising flow1 which is notoriously hard for traditional normalising flows?

One possible answer to that is to use Flow Matching, a kind of algorithm between normalising flows and diffusion models. The TLDR of flow matching is to model the vector field describing how samples go from a simple base distribution into some more complicated distribution. The basic idea is shown in the GIF below which I stole from “An introduction to Flow Matching” by Tor Fjelde, Emile Mathieu, and Vincent Dutordoir.

But this post isn’t titled an introduction to flow matching, it’s on continuous normalising flows. Continous flows can be thought of as a kind of precursor or fundamental component (depending on how you look at it) to Flow Matching. But, they are also very cool in their own right and make some cool looking gifs2.

Core Idea

Following the same logical flow as the original continous normalising flows paper, annoyingly called “Neural Ordinary Differential Equations”3, we begin by describing residual normalising flows or semi-equivalently residual neural networks.

Residual neural networks are networks were sequential layers try to model additive changes to the output of the previous layer rather than strictly just taking the previous layer as an input and pumping out a new output. e.g.

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{h}_{t+1} = \mathbf{h}_t + f(\mathbf{h_t}, \mathbf{\theta}_t), \end{align}\]where \(t\) is some discrete value that indicates the depth of the network. Additionally you could view normalising flows such as RealNVP with just additive transformations (e.g. unity scaling) as some form of this,

\[\begin{align}z_{t+1}^i = z_t^i + f(\mathbf{z_t}^{1:d}, \mathbf{\theta}_t),\end{align}\]for \(i>d\). The amazing thing that Chen et al. 2019 noticed is that this is extremely similar to an Euler discretised solution to some continuous transformation. Taking the number of the steps to infinity/take smaller steps we can imagine that in the limit we recover some quasi-ODE of the form,

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{dt} = f(\mathbf{z}(t), t, \mathbf{\theta}). \end{align}\]Applying this directly to our flow, we can view time \(t=0\) as the distribution of samples or probability under our base distribution (e.g. normal) and our final time, which we’ll just denote as \(t_f\), as the distribution of samples/probability under our target distribution. Once we have it in this form we can then just chuck our favourite black box ODE solver at it.

There are many fantastic things about this, the three ones that are of interest to me are:

- Memory efficiency. Unlike a traditional normalising flow, increasing the “complexity” of our transformations does not increase our memory cost, just possible training time. i.e. we get a constant memory cost necessarily (not something you get from deep neural networks)

- Adaptive computation. Using an ODE solver to solve our transformation allows adaptive computation of the accuracy and tolerance of our solution with many modern ODE solvers being able to adaptively adjust step-size to manage error.

- Normalising flow scalability. On top of the roughly constant memory cost, reparameterising our problem into this form means that our jacobians/change of variables is easier/quicker to compute and the forward and reverse directions of evaluating our flow become roughly equal in cost unlike methods, such as autoregressive models, that have a particular direction with faster computation, while still having great flexibility.

‘Ground Up’ CNF

I’m going to skip some of the details relating to the backpropagation of the parameters being trained and skip straight into coding up an example that is basically a re-work of the example by Ricky Chen4 stored on github here.

Analogous to a planar normalising flow, described as,

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{z}(t+1) &= \mathbf{z}(t) + h\left(w^T \mathbf{z}(t) + b \right), \\ \log p(\mathbf{z}(t+1)) &= \log p(\mathbf{z}(t)) - \log \left\vert 1 + u^T \frac{\partial h}{\partial \mathbf{z}}\right\vert, \end{align}\]we’re going to initially be interested in the system defined as,

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{dt} = u \cdot h\left(w^T \mathbf{z}(t) + b \right), \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} = -u^T \frac{\partial h}{\partial \mathbf{z}(t)}. \end{align}\]So the parameters that we need to learn are those of \(u\), \(w\) and \(b\), that are a functions of just \(t\).

Just to get some boring stuff out of the way, here are most of imports for the post.

import os

import argparse

import glob

from PIL import Image

import numpy as np

import matplotlib

matplotlib.use('agg')

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn.datasets import make_circles, make_swiss_roll # yes a swiss roll

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torch.optim as optim

results_dir = "./results"

For the actual code for the continuous normalising flow, which from now on I’ll just call CNF not to be confused with conditional normalising flows, the forward model is stupid simple. We just need to take in a time, the state of the samples/probabilities.

def forward(self, t, states):

z = states[0]

logp_z = states[1]

Then because of the ODE solver that we will be using later on from torchdiffeq requires it for some internals basically, we’re going to enforce gradient tracking.

with torch.set_grad_enabled(True):

z.requires_grad_(True)

We’ll then off-load the calculation of the \(w\), \(b\) and \(u\) to a dedicated neural network.

# Neural network to model the vector field

W, B, U = self.hyper_net(t)

Then because we’re actually dealing with matrices in practice, specifically

- \(z\) will have the dimensionality of the distribution we’re trying to model and the number of samples we want to estimate the expectation value from the loss

- e.g. 2D posterior with 300 monte carlo samples »

z.shape = (300, 2),

- e.g. 2D posterior with 300 monte carlo samples »

- and then \(u\), \(w\) and \(b\) will have the dimensionality of the distribution we’re trying to model and the width in the neural network’s output we’re using to model these.

- e.g. above + width of 64 »

w.shape = (64, 2, 1)&b.shape = (64, 1, 1)&u.shape = (64, 1, 2)(the 2s being there for sake of the distributions’ dimensionality)

- e.g. above + width of 64 »

So we’ll expand \(z\) so that it has compatible shapes for the multiplication with \(w\).

Z = torch.unsqueeze(z, 0).repeat(self.width, 1, 1)

We then do what we came for and calculate \(\frac{dz}{dt}\) using \(\tanh\) for our ‘kind of’ activation function \(h\) averaging over the dimension of ‘width’.

h = torch.tanh(torch.matmul(Z, W) + B)

dz_dt = torch.matmul(h, U).mean(0)

Then we want to calculate the derivative of the probability with respect to time so that we can get a functional form of our probabilities, as we usually do with flows, noting that,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} = -\textrm{tr}\left( \frac{df}{d\mathbf{z}(t)}\right). \end{align}\]Which proving right now will get in the way of the result, so I’ll just promise to prove that later, and you’re just gonna have to trust me for now.

Our starting point for all this was \(\frac{d\mathbf{z}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{z}(t), t, \mathbf{\theta})\), using this we can see \(\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}(t)} = \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}(t)} \frac{d\mathbf{z}}{dt}\). We can do this with torch.autograd.grad which is broadly plug-n-chug. I’ll however note that,

- the

create_graph=Trueoption allows higher order derivatives to be calculated later on - that you can think of the jacobian as an outer product of the vector input and vector derivative, and hence we single out each dimension of \(z\) when taking the derivative

dz_dt[:, i]but later on slice into this to get the diagonal term(s)...aph=True)[0][:, i] - remember that the first dim of

dz_dtis over the number of samples, for which we need to do these calculations for each independently

trace_df_dz = 0.

for i in range(z.shape[1]):

trace_df_dz += torch.autograd.grad(dz_dt[:, i].sum(), z, create_graph=True)[0][:, i]

dlogp_z_dt = - trace_df_dz.view(batchsize, 1) # some other reshaping fun stuff

And badabing we have our CNF, copy-pasted here so you can look at it in full (and see how simple it is at the end of the day).

class CNF(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_out_dim, hidden_dim, width):

super().__init__()

self.in_out_dim = in_out_dim

self.hidden_dim = hidden_dim

self.width = width

self.hyper_net = HyperNetwork(in_out_dim, hidden_dim, width)

def forward(self, t, states):

z = states[0]

logp_z = states[1]

batchsize = z.shape[0]

with torch.set_grad_enabled(True):

z.requires_grad_(True)

# Neural network to model the vector field

w, b, u = self.hyper_net(t)

Z = torch.unsqueeze(z, 0).repeat(self.width, 1, 1)

h = torch.tanh(torch.matmul(Z, w) + b)

dz_dt = torch.matmul(h, u).mean(0)

# calculating the trace

trace_df_dz = 0.

for i in range(z.shape[1]):

trace_df_dz += torch.autograd.grad(dz_dt[:, i].sum(), z, create_graph=True)[0][:, i]

dlogp_z_dt = - trace_df_dz.view(batchsize, 1)

return (dz_dt, dlogp_z_dt)

I’ll then rush through the creation of that dedicated neural network because it’s essentially just

- single dim input (\(t\))

- do some neural network stuff

- slice into the neural network outputs to get \(w\), \(b\), \(u\) (capitalised) with the modelling of an extra internal variable

Gto stabilise the values for \(u\).

class HyperNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_out_dim, hidden_dim, width):

super().__init__()

blocksize = width * in_out_dim

self.fc1 = nn.Linear(1, hidden_dim)

self.fc2 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim)

self.fc3 = nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 3 * blocksize + width)

self.in_out_dim = in_out_dim

self.hidden_dim = hidden_dim

self.width = width

self.blocksize = blocksize

def forward(self, t):

# predict params

params = t.reshape(1, 1)

params = torch.tanh(self.fc1(params))

params = torch.tanh(self.fc2(params))

params = self.fc3(params)

# restructure

params = params.reshape(-1)

W = params[:self.blocksize].reshape(self.width, self.in_out_dim, 1)

U = params[self.blocksize:2 * self.blocksize].reshape(self.width, 1, self.in_out_dim)

G = params[2 * self.blocksize:3 * self.blocksize].reshape(self.width, 1, self.in_out_dim)

U = U * torch.sigmoid(G)

B = params[3 * self.blocksize:].reshape(self.width, 1, 1)

return [W, B, U]

Training our CNF

To make the loss simpler, as I showed in my post on building a normalising flow from scratch, we’ll presume that we’re trying to estimate the probability distribution from a set of samples from some target distribution. Reducing our loss to effectively being,

\[\begin{align} \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{\theta}) \approx -\frac{1}{N} \sum_i^N \log q_{\mathbf{z}}(\mathbf{z}_i\vert\mathbf{\theta}). \end{align}\]We’ll try and model 4 rings of samples.

def get_dist_samples(num_samples):

points1, _ = make_circles(n_samples=num_samples//2, noise=0.06, factor=0.5)

points2, _ = make_circles(n_samples=num_samples//2, noise=0.03, factor=0.5)

points2*=4

points = np.vstack((points1, points2))

x = torch.tensor(points).type(torch.float32).to(device)

logp_diff_t1 = torch.zeros(num_samples, 1).type(torch.float32).to(device)

return (x, logp_diff_t1)

z, logp_diff_t1 = get_dist_samples(num_samples=100000)

We will use an ODE solver/integrator from torchdiffeq called odeint_adjoint. All it does (at least as far as we’ll discuss for now) is take some input \(\frac{df}{dt}\) and integrates it over \(t\).

from torchdiffeq import odeint_adjoint as odeint

We’ll then initialise an example model, our start and end “times”, the optimiser we want to use (Adam) with a learning rate of 0.02, our base distribution (2D normal) and something to keep track of the loss later (doesn’t have anything to do with the actual implementation of the CNF)

t0 = 0

t1 = 10

device = torch.device('cpu')

losses = []

cnf_func = CNF(in_out_dim=2, hidden_dim=32, width=64).to(device)

optimizer = optim.Adam(cnf_func.parameters(), lr=1e-2)

# base distribution for "z at time 0" hence z0

p_z0 = torch.distributions.MultivariateNormal(

loc=torch.tensor([0.0, 0.0]).to(device),

covariance_matrix=torch.tensor([[0.1, 0.0], [0.0, 0.1]]).to(device)

)

# thing to keep track of loss that isn't necessarily required

loss_meter = RunningAverageMeter()

For our training we’ll specify the number of iterations we want…iterating over them. We’ll turn off the gradients so that we have control over specifically where we’ll track gradients otherwise some inefficiencies may pop up.

niters = 1000

for itr in range(1, niters + 1):

optimizer.zero_grad()

We’ll grab some samples from our target distribution, specifically 300, because from some of my own testing, that’s as many I could use before I couldn’t be bothered waiting for the training to finish. Also outputting an empty array that we can use for tracking the derivatives of the log probabilities.

x, logp_diff_t1 = get_dist_samples(num_samples=300)

We then chuck our

- CNF function/model

- distribution samples and dummy probability to transform

- our end and start times

- our tolerances for the accuracy of the ODE solver (

rtolandatol) - and the general method that we want the ODE solver to use, which I’m picking to be the Runge-Kutta-Fehlberg method into our ODE solver to get our transformed samples and transformation jacobian.

z_t, logp_diff_t = odeint(

func,

(x, logp_diff_t1),

torch.tensor([t1, t0]).type(torch.float32).to(device),

atol=1e-5,

rtol=1e-5,

method='fehlberg2',

)

# Picking the samples and probabilities in the base distribution space

z_t0, logp_diff_t0 = z_t[-1], logp_diff_t[-1]

# log probabilities of our CNF model on the target distribution samples

# our equivalently the probabilities under our base distribution of the reverse

# transformed samples and the jacobian for the transformation

logp_x = p_z0.log_prob(z_t0).to(device) - logp_diff_t0.view(-1)

We then calculate our loss using the equation above.

loss = -logp_x.mean(0)

And then backwards propagate the model parameters and take a step with our optimiser.

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# Keeping track of the losses using the running meter

loss_meter.update(loss.item())

# Keeping track of the average losses with a basic list

losses.append(loss_meter.avg)

In total, the training looks like this, with some division between actual mathematical steps and general neural network training.

niters = 1000

for itr in range(1, niters + 1):

optimizer.zero_grad()

x, logp_diff_t1 = get_dist_samples(num_samples=300)

############################################################

############################################################

##### Solve ODE and calculate loss

z_t, logp_diff_t = odeint(

func,

(x, logp_diff_t1),

torch.tensor([t1, t0]).type(torch.float32).to(device),

atol=1e-5,

rtol=1e-5,

method='fehlberg2',

)

z_t0, logp_diff_t0 = z_t[-1], logp_diff_t[-1]

logp_x = p_z0.log_prob(z_t0).to(device) - logp_diff_t0.view(-1)

loss = -logp_x.mean(0)

############################################################

############################################################

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

loss_meter.update(loss.item())

losses.append(loss_meter.avg)

print('Iter: {}, running avg loss: {:.4f}'.format(itr, loss_meter.avg))

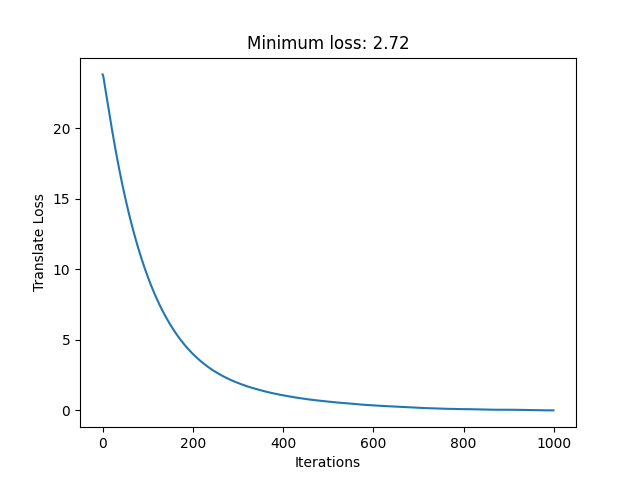

From this I get the following loss curve.

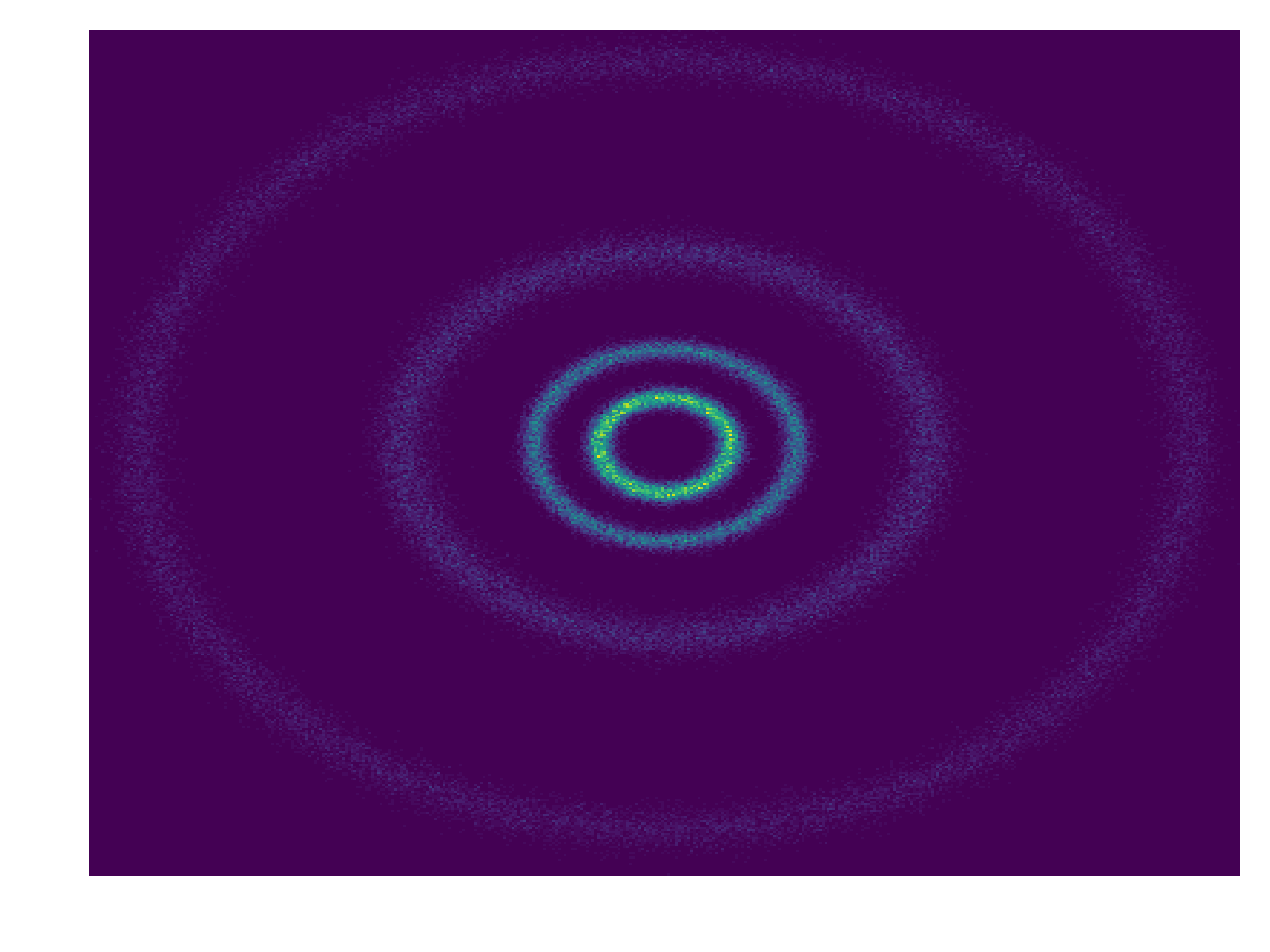

And then what we really came for, how well our CNF actually did to approximate our sample distribution!

And I would just like to emphasize, this is not a training animation, this is actually how the samples are transformed from our assumed base distribution to our target distribution.

Proof of det Jacobian trace derivative

Chen et al. 2019 also produce this proof but put it into one of the appendices, but personally I would have liked it in the main body, as to me it really came out of left field. Hence…

What we want to prove (in less rigour than the original paper, so head on over there if you want more of that) is that for am ODE defined as (omitting transformation variables \(\mathbf{\theta}\) )

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\mathbf{z}}{dt} = f(\mathbf{z}(t), t) \end{align}\]with \(\mathbf{z}\) being a continuous random variable with probability density \(p(\mathbf{z}(t))\), then,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} = -\textrm{tr}\left(\frac{df}{d\mathbf{z}}(t)\right). \end{align}\]To prove this we’ll first introduce \(T_\epsilon\) which you can think of as \(f(\mathbf{z}(t), t)\) integrated over time \(\delta t = \epsilon\) such that,

\[\begin{align} \mathbf{z}(t+\epsilon) = T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \end{align}\]Assuming nothing about \(f\), \(T_\epsilon\) or \(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}}T_\epsilon\), we can say among other things (probably somewhat obviously),

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \mathbf{z}(t) &= 1 \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \log(\mathbf{z}(t)) |_{\mathbf{z}=\mathbf{1}} &= \frac{\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \mathbf{z}(t)}{\mathbf{z}(t)} |_{\mathbf{z}=\mathbf{1}} = \frac{1}{\mathbf{z}(t)} |_{\mathbf{z}=\mathbf{1}} = \mathbf{1} \\ \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \epsilon = 1. \end{align}\]If \(\epsilon\) goes to 0, then the transformation becomes the identity or,

\[\begin{align} \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) &= \mathbf{1} \\ \therefore \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert &= 1 \\ \therefore \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{1}{\left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert} &= 1. \end{align}\]Hence (equations 15-20 in Chen et al. 2019),

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} &= \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{ \log p(\mathbf{z}(t+\epsilon)) - \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\epsilon}\\ &= \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{ \log p(\mathbf{z}(t)) - \log \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert - \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\epsilon} \hspace{2em} \textrm{(basic taylor expansion)} \\ &= - \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{ \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \log \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert}{ \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \epsilon} \hspace{2em} \textrm{(L'Hôpital's rule)} \\ &= - \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{ \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert}{ \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert} \\ &= - \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert \cdot \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{1}{ \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert} \\ &= - \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert \end{align}\]And then unfortunately I’m going to just state a theorem and leave it up to you to investigate more if you aren’t satisfied with the levels of detail I’ve shown, as this may come as a surprise to you, I do not want to axiomatically prove all of math in this blog post. The method is called Jacobi’s formula,

\[\begin{align} \frac{d}{dt} \det A(t) = \textrm{tr}\left(\textrm{adj}(A(t)) \frac{d A(t)}{dt} \right) . \end{align}\]This allows us to further manipulate our derivative above as,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} &= - \lim_{\epsilon\rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \left\vert \det \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t))\right\vert \\ &= - \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \textrm{tr}\left(\textrm{adj}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right) \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left( \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \textrm{adj}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right) \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left( \left(\lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \textrm{adj}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right)\right) \left(\lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right)\right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left(\lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} T_\epsilon(\mathbf{z}(t)) \right) \\ \end{align}\]The final part of this proof is to then just Taylor expand \(T_\epsilon\) about \(\epsilon\),

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \log p(\mathbf{z}(t))}{\partial t} &= - \textrm{tr}\left( \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \left(\mathbf{z} + \epsilon f(\mathbf{z}(t), t) + \mathcal{O}(\epsilon^2) \right)\right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left( \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \frac{\partial}{\partial \epsilon} \left(\mathbf{I}+ \epsilon \frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} f(\mathbf{z}(t), t) + \mathcal{O}(\epsilon^2) \right)\right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left( \lim_{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+} \left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} f(\mathbf{z}(t), t) + \mathcal{O}(\epsilon) \right)\right) \\ &= - \textrm{tr}\left(\frac{\partial}{\partial \mathbf{z}} f(\mathbf{z}(t), t) \right) \\ \end{align}\]The Adjoint Method

The key difficulty that Chen et al. 2019 highlight for this method, is backpropagating our derivatives through this kind of system. Debatably the main achievement of the paper is to introduce the use of the adjoint method for “reverse-mode” automatic differentiation/backpropagation that alleviates some of the introduced inefficiencies regardless of the ODE solver used5.

We treat the ODE solver as just some function \(\textrm{ODESolve}\) that takes in the initial state \(z(t_0)\), the initial time \(t_0\), final time \(t_1\) and parameters of \(f\), \(\mathbf{\theta}\). The loss which is calculated based on the final state this translates to,

\[\begin{align} L(\mathbf{z}(t_1)) &= L\left(\mathbf{z}(t_0) + \int_{t_0}^{t_1} f(\mathbf{z}(t), t, \theta) dt \right) \\ &= L\left(\textrm{ODESolve}(\mathbf{z}(t_0), f, t_0, t_1, \mathbf{\theta})\right). \end{align}\]Normally, we would then blindly apply automatic differentiation of our loss \(L\) with respect to the parameters being trained \(\mathbf{\theta}\) but again, this would have to go through the solver. The key idea of the adjoint method is that instead of this, you get the derivatives by solving for the dynamics of a separate quantity \(a(t)\) and it will give you,

\[\begin{align} \frac{dL}{d\theta} = - \int_{t_0}^{t_1} a(t)^T \frac{\partial f(\mathbf{z}(t), t, \theta)}{\partial \mathbf{\theta}} dt. \end{align}\]This can be done simultaneously to \(\mathbf{z}(t)\) by the same solver as it requires the same information as is required for \(\mathbf{z}(t)\).

Thank you so much Vaibhav Patel6 for their post on Deriving the Adjoint Equation for Neural ODEs using Lagrange Multipliers for helping me with the following. We can set up our system as finding the set of values \(\mathbf{\theta}\) that minimise our loss, subject to the constraint,

\[\begin{align} F\left(\frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{dt}, \mathbf{z}(t), \mathbf{\theta}, t\right) = \frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{dt} - f(\mathbf{z}(t), \mathbf{\theta}, t) = 0. \end{align}\]We can make this more applicable by translating it into terms involving our loss function,

\[\begin{align} \psi(\mathbf{\theta}) = L(\mathbf{z}(t_1)) - \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \mathbf{a}(t)F\left(\frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{dt}, \mathbf{z}(t), \mathbf{\theta}, t\right) dt, \end{align}\]introducing the time dependent Lagrange multipler. If we take a gradient of this with respect to \(\theta\) we see that,

\[\begin{align} \frac{d\psi}{d\theta} = \frac{dL(\mathbf{z}(t_1))}{d\theta}, \end{align}\]as we know by construction that \(F=0\). The benefit to doing all this is to choose \(\mathbf{a}(t)\) to eliminate computationally difficult terms in \(dL/d\mathbf{\theta}\). e.g. the most complicated derivative we could take \(d\mathbf{z}(t_1)/d\mathbf{\theta}\). I’m going to tell you to jump over to Patel’s post for the following,

\[\begin{align} \frac{dL}{d\theta} &= \left[\frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{z}(t_1)} - \mathbf{a}(t_1)\right]\frac{d\mathbf{z}(t_1)}{d\mathbf{\theta}}\\ & + \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \left(\frac{d\mathbf{a}(t)}{dt}+\mathbf{a}(t)\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}} \right) \frac{d\mathbf{z}(t)}{d\mathbf{\theta}} dt\\ & + \int_{t_0}^{t_1} \mathbf{a}(t)\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{\theta}} dt . \end{align}\]Based on the fact that we don’t want to have to evaluate \(d\mathbf{z}(t_1)/d\mathbf{\theta}\), we want to get rid of both of the first terms. This means that we want,

\[\begin{align} a(t_1) = \frac{\partial L}{\partial \mathbf{z}(t_1)} \end{align}\]and,

\[\begin{align} &\frac{da(t)}{dt}= -a(t)\frac{\partial f}{\partial \mathbf{z}}. \\ \end{align}\]Then once the first two terms are cancelled out, and additionally flipping the direction of the integral, you arrive at Equation 5 of Chen et al. 2019 allowing us to efficiently calculate derivatives of the loss with respect to our training parameters regardless of the specifics of the ODE solver,

\[\begin{align} \frac{dL}{dt} = - \int_{t_1}^{t_0} \mathbf{a}(t)\frac{\partial f(\mathbf{z}(t), t, \mathbf{\theta})}{\partial \mathbf{\theta}} dt. \end{align}\]And thankfully, at least as a user, we never have to worry about this as various python packages including torchdiffeq, which I used for my above code examples, have solvers with this baked in (e.g. torchdiffeq’s odeint_adjoint).

Conclusion

Hopefully you now better understand continuous normalising flows for variational inference, for a follow up I would recommend directly reading through Patel’s post on the adjoint method, and Chen et al. 2019 (should be easier to read now).

EDIT: 09/08/2025

Just had another look at Patel’s website and saw he has another post on the computational efficiency on the vector jacobian product that you should also definitely have a look at!

Appendices

Proof of Jacobi’s formula

As I stated above, I’m basically just yoinking this from Wikpedia, feel free to skip this and head over there.

So, what we want to show is,

\[\begin{align} d \det (A) = \textrm{tr}\left(\textrm{adj}(A) dA \right) \end{align}\]where \(t\) is continuous and \(A\) is some differentiable map to \(n \times n\) matrices.

Hopefully, you’re at least vaguely familiar with Laplace’s formula for calculating determinants7 that gives,

\[\begin{align} \det (A) = \sum_j A_{ij} \, \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ij}. \end{align}\]In which case the proof is pretty straight forward, starting with just a general differential of the determinant

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \det(A)}{\partial A_{ij}} &= \sum_j \frac{\partial}{\partial A_{ij}} \left( A_{ik} \, \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik} \right) \\ &= \sum_j \frac{\partial A_{ik}}{\partial A_{ij}} \, \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik} + \sum_j A_{ik} \, \frac{\partial}{\partial A_{ij}} \left( \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik} \right) \\ \end{align}\]The adjoint \(\textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik}\) can be derived as the determinant of the parts of the matrix not in the row \(i\) or column \(k\), and thus if \(j=k\) then \(\textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik}\) will by pretty much by definition not involve \(A_{ij}\) (as they will either share \(i\) or \(j\)), hence,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik}}{\partial A_{ij}} = 0. \end{align}\]Simplifying our formula to,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \det(A)}{\partial A_{ij}} &= \sum_j \frac{\partial A_{ik}}{\partial A_{ij}} \, \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik}. \end{align}\]This can further be simplified as \(\frac{\partial A_{ik}}{\partial A_{ij}}\) can only be non-zero if \(A_{ik} = A_{ij}\) otherwise you’re just taking derivatives with respect to unrelated quantities. Hence,

\[\begin{align} \frac{\partial \det(A)}{\partial A_{ij}} = \sum_j \delta_{jk} \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ik} = \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ij}. \end{align}\]And by chain rule you can see that,

\[\begin{align} d\left( \det(A)\right) &= \sum_i \sum_j \frac{\partial \det(A)}{\partial A_{ij}} dA_{ij} \\ &= \sum_i \sum_j \textrm{adj}^T(A)_{ij} dA_{ij} \\ &= \sum_i \sum_j \textrm{adj}(A)_{ji} dA_{ij} \hspace{1em} \textrm{(expanding the transpose)}\\ &= \sum_j \left(\textrm{adj}(A) dA \right)_{jj} \hspace{2.4em} \textrm{(tis how matrix multiplication works)}\\ &= \textrm{tr}\left(\textrm{adj}(A) dA \right) \hspace{3.8em} \textrm{(definition of the trace)}. \end{align}\]a type of flow that can produce \(p(y\vert x)\). Modelling both \(y\) and \(x\) ↩

the real purpose of any scientific endeavour being the generation of cool gifs of course (joke) ↩

Not actually annoying because the key concept was to replace traditional neural networks with these kinds of systems. ↩

First author for the original Neural Ordinary Differential Equations ↩

Or in their own words for “black box” ODE solvers. Referring to the fact that you don’t need to know about the internals of the ODE solver to use this method. ↩

And thank you Sam Foster you magnificent beast for your help as well. ↩

I would link to a better source for the derivation but I can’t find a nicely accessible one besides this for now. ↩