Markov Chain (+) Monte Carlo methods

Published:

In this post, I’ll go through “What is MCMC?”, “How is it useful for statistical inference?”, and the conditions under which it is stable.

Resources

As usual, here are some other resources if you don’t like mine.

- The algorithm that (eventually) revolutionized statistics - Very Normal

- Focuses on Metropolis-Hastings algorithm but briefly dives into MCMC and detailed balance

- Crash Course on Monte Carlo Simulation - Very Normal

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC): Data Science Concepts - ritvikmath

- Markov Chains Clearly Explained! Part - 1

- Markov Chains Clearly Explained! Part - 2

- Markov Chains: n-step Transition Matrix | Part - 3

- Markov Chains: Data Science Basics - ritvikmath

- Monte Carlo Simulations: Data Science Basics - ritvikmath

- A Conceptual Introduction to Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods - Joshua S. Speagle

- An effective introduction to the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method - Wenlong Wang

- Detailed Balance

- Stationary Distributions of Markov Chains - Today’s sponsor is Brilliant.org1

- Monte Carlo Methods - Dirk P. Kroese, Reuven T. Rubinstein

Table of Contents

What is MCMC?

MCMC stands for “Markov Chain Monte Carlo,” which actually details the combination of two separate (but more often than not combined) ideas of “Markov Chains” and “Monte Carlo methods” that simulate data to approximate distributions of interest. In the case of Markov Chains, we are generally interested in the “equilibrium distribution” or “equilibrium state,” and Monte Carlo methods are a broad category of methods that use random sampling to analyse the behaviour of distributions2. I’ll attempt to introduce both separately but then cover some important notes on the “MCMC,” circling back to the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm for a bit as well.

Markov Chains

To introduce this, I’m going to closely follow an example from one of the (VCE) General Mathematics3 textbooks that I use with students.

Let’s say that you own a one-day rental car company that has two branches in the towns of Colac and Bendigo (trust me, we’ll get back to probability distributions in a minute).

The towns are close enough such that many customers like to return their cars to a different branch to the one they picked them up from.

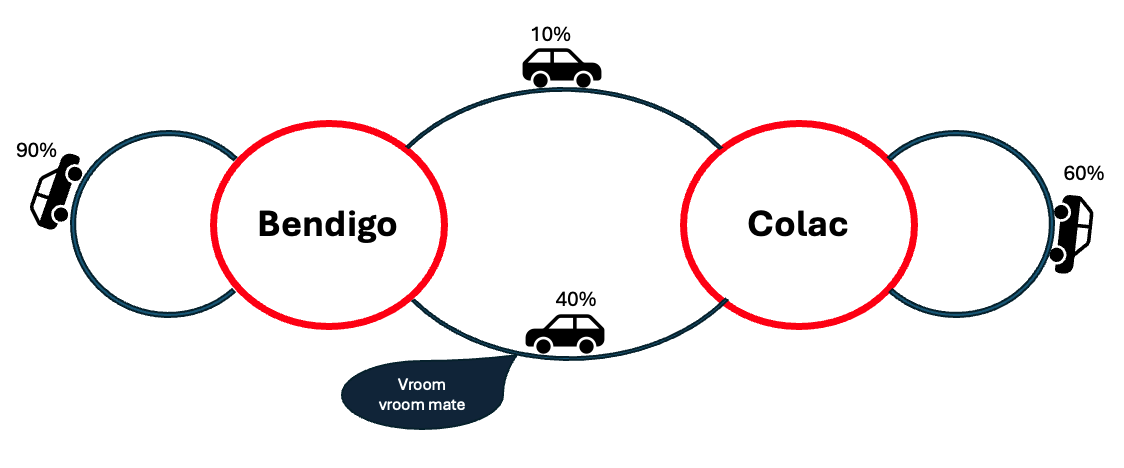

Specifically, you estimate that 40% of the cars in Colac are dropped off in Bendigo because the number of people that live around Bendigo is larger, and similarly, only 10% of cars from Bendigo are dropped off at Colac because the general population of Colac is that much smaller than Bendigo.

From this, we can see that 60% of the cars in Colac are dropped off at Colac, and 90% of the cars in Bendigo stay in Bendigo.

This is a lot simpler to see from the below (very sophisticated) diagram (that I definitely didn’t screenshot from PowerPoint).

You then have a client who has left something in the car they rented but you’ve lost track of the records. You don’t want to waste your time searching all the cars in each branch, so you at least want to know which branch is more likely to have the car.

The renter at least remembers which dealership they dropped the car off at: Colac. We can represent this state in time as a 2x1 matrix.

\[\begin{align} S_0 = \left[ \begin{matrix} \text{# in Colac}\\ \text{# in Bendigo} \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} 1\\ 0 \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\]Very unhelpfully, it is also unclear how many days/weeks/months/years it has been since they returned the car, all you can assume is that it’s been “a long time”… (at this point you may be wondering whether this person even rented a car from you in the first place, but let’s assume that they did in fact rent a car)

The first thing that we’re going to do is translate the picture into a transition matrix that will mathematically represent how one day/state (e.g., the 2x1 matrix above) will transform into the next4.

\[\begin{align} T = \left[ \begin{matrix} \text{Colac $\rightarrow$ Colac} & \text{Bendigo $\rightarrow$ Colac}\\ \text{Colac $\rightarrow$ Bendigo} & \text{Bendigo $\rightarrow$ Bendigo} \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6 & 0.1\\ 0.4 & 0.9 \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\]The main thing to notice here is that the columns sum to 1, as the numbers represent the fraction of cars moving from one town to another, and you can’t have that 70% stay and 70% transfer5. This also allows us to have a probabilistic interpretation of our results. So, presuming that the day the renter returned their car is “Day 0,” then Day 1 can be expressed

\[\begin{align} S_1 = T \, S_0 = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6 & 0.1\\ 0.4 & 0.9 \end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} 1\\ 0 \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6\\ 0.4 \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\]So we can interpret this as ‘there is a 60% chance that the car is in Colac and a 40% chance it’s in Bendigo,’ and this will be our “state” for that day. Thinking in terms of probability now instead of number of cars. Now, stick with me, we’ll look at the state of the next day.

\[\begin{align} S_2 = T \, S_1 = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6 & 0.1\\ 0.4 & 0.9 \end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6\\ 0.4 \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.4\\ 0.6 \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\]And here you can clearly see that \(S_2 = T \, S_1 = T^2 S_0\), and in general \(S_n = T^n S_0\). And now, I will painstakingly calculate some later state matrices until we see something interesting.

Code

import numpy as np

initial_state_matrix = np.array([1,0]).T

transition_matrix = np.array([[0.6, 0.1], [0.4, 0.9]])

day_i = np.matmul(np.linalg.matrix_power(transition_matrix, 10), initial_state_matrix)

day_i, day_i.shape

Well, that’s interesting (at least to me). We call this state that remains the ‘steady-‘ or ‘equilibrium-‘ state, often denoted with the subscript \(S\), or with an infinity to denote it is the matrix that will occur after an infinite number of transitions, \(S_{\infty}\)6. It is this state in the “chain” of events that is a key characteristic of Markov Chains, which the above situation is an example of. And just to finish the example off, we should likely investigate the Bendigo branch first, as in the long run there is an 80% chance of the car being there. I like the equilibrium definition of the state as it reminds me of a pendulum coming to rest, and now matter how much you perturb it, it has “a state” that it will “rest” in after which it won’t move anymore.

If you apply the transition matrix, \(T\), to this state, you can see that we get the same state back.

\[\begin{align} S = T\, S = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.6 & 0.1\\ 0.4 & 0.9 \end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.2\\ 0.8 \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} 0.2\\ 0.8 \end{matrix} \right] \end{align}\]A strict definition of a Markov chain

A Markov chain is a stochastic process that involves transitions between some notion of states7, where the next state depends only on its immediate predecessor8.

It allows the user to investigate systems (physical, statistical, or a mix of both), particularly those that have some sort of equilibrium where the process will converge. In the above, you can see the immediate ability to investigate probability distributions, but “so what,” you might ask. Sure, I can see how one state can progress to the next, but how does that help me represent a distribution? I will delay this until after I also discuss Monte Carlo methods. For now, another question you might be having is “when is there an equilibrium state?”

Detailed Balance

Detailed balance is a condition that ensures that (but is not required for) Markov Chains converge to the target distribution over time9. It requires that for a Markov process with transitions from state \(i\) to state \(j\) are described by the transition matrix \(P_{ij}\), that for a discrete state space (like above)10:

\[\begin{align} P_{ij}S_i = P_{ji} S_j \end{align}\]and for a continuous state space where \(\pi(s)\) describes a particular state governed by the probability distribution \(\pi\) and the transition matrix turns into the transition probability or kernel from state \(i\) to state \(j\),

\[\begin{align} P(s_i\mid s_j)\pi(s_i) = P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_j). \end{align}\]If you further restrict your transition probabilities to those that are symmetric (\(P_{ij} = P_{ji}\) for the discrete case or \(P(s_i \mid s_j) = P(s_i \mid s_j)\) for the continuous case), then detailed balance is automatically satisfied, as then the stationary state is just a uniform distribution over the whole state space (as going from any point is as probable as going to any other point → all states are equally probable).

More colloquially, detailed balance also ensures the reversibility of the process, where the “flow” of probabilities going into and out of states is the same. In my car rental example, this means that the number of cars flowing into Colac from Bendigo is the same as the number going out from Colac to Bendigo.

How does Metropolis-Hastings satisfy detailed balance?

But now you might be confused, because in a previous post I said that the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm (an example of an MCMC algorithm, hence utilises Markov chains) will automatically work when you give it a symmetric proposal distribution, but very rarely do we run MCMC on uniform distributions or get uniform samples out of it. So what gives?

Well, the transition probability in the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm is not just the proposal distribution’s conditional probability distribution \(q(s_i\mid s_j)\), but the product of the conditional probability and the acceptance probability \(A(s_i \rightarrow s_j)\). And if the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm always satisfies detailed balance, which we can see because it does eventually converge on the target probability distribution even if it takes infinite time11, then why can we use an asymmetric proposal and the seemingly asymmetric acceptance probabilities? Well, it’s actually quite nice and simple when you explore the math12.

Let’s say the target probability distribution is \(\pi\). With \(P(s_i \mid s_j)\) representing the probability to transition to state \(s_j\) given that we are currently at state \(s_i\), then we see,

\[\begin{align} P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) = q(s_j \mid s_i) \pi(s_i) A(s_i \rightarrow s_j) = q(s_j \mid s_i) \pi(s_i) \min\left(1, \frac{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)}{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}\right). \end{align}\]The minimum function then gives us two cases.

Case 1: minimum = 1 < \(\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)/\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)\)

\[\begin{align} P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) &= q(s_j \mid s_i) \pi(s_i) \cdot 1 \\ &= q(s_j \mid s_i) \pi(s_i) \cdot \frac{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)}{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)} \cdot \frac{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)} \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \cdot \frac{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)} \end{align}\]Then because if \(\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)/\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i) > 1\) then \(\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)/\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) < 1\), hence,

\[\begin{align} P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) &= q(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) \cdot 1 \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \cdot \frac{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)} \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \min\left(1, \frac{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)} \right)\\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) A(s_j \rightarrow s_i)\\ &= \pi(s_j) P(s_j \mid s_i). \end{align}\]Case 2: minimum = \(\mathbf{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)/\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)} < 1\)

\[\begin{align} P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) &= q(s_j \mid s_i) \pi(s_i) \cdot \frac{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)}{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)} \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \end{align}\]Then similar to the other case but reverse, if \(\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)/\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i) < 1\) then \(\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)/\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) > 1\), hence,

\[\begin{align} P(s_i \mid s_j) \pi(s_i) &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) \min\left(1, \frac{\pi(s_i)q(s_j\mid s_i)}{\pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j)}\right) \\ &= \pi(s_j)q(s_i\mid s_j) A(s_j \rightarrow s_i)\\ &= \pi(s_j) P(s_j \mid s_i). \end{align}\]Yay

So, even if the proposal distribution is asymmetric, by the modification of the acceptance probability compared to the Metropolis algorithm, the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm always satisfies detailed balance, meaning that there exists a stationary distribution, and due to the stochastic nature of the algorithm, it will eventually find it. This absolutely does not mean it will find it within the timeframe that you require, or that what you think is the equilibrium distribution is actually the equilibrium distribution. I will talk more on this when I get to diagnostics you can run on MCMC.

I’ll leave it to you to see how the original Metropolis algorithm13 satisfies detailed balance.

Monte Carlo (gambling) methods

Now that we’ve explored Markov Chains, let’s shift gears and look at Monte Carlo methods, the second half of MCMC. These methods rely on random sampling to approximate solutions to complex problems14; the obvious case is Metropolis-Hastings. They are often employed in simulations, integration, and optimization tasks. To show that Markov Chains and Monte Carlo methods are in fact distinct, I’ll use a few other examples of methods that fall in this category, as the above definition is really it.

Examples

Example 1: Flipping a coin

The main basis behind most Monte Carlo methods is that you wish to simulate samples of some distribution. The most boring example of this is drawing a large set of random, uniformly distributed samples between 0 and 1; you then assign values below 0.5 to Heads and above to Tails, thus simulating the distribution of outcomes for repeated flips of a fair coin.

Example 2: \(\pi\)

Another neat example is estimating \(\pi\) by:

- generating two sets of samples that follow a uniform distribution between 0 and 1 (let’s call them \(x\) and \(y\));

- seeing how many samples satisfy \(dist((0,0), (x,y)) = \sqrt{x^2+y^2} \leq 1\). The proportion of samples geometrically should be \(\pi/4\);

- dividing the number of samples satisfying the criteria by the total number of samples and multiplying by 4 should give you an estimate of \(\pi\)!

Code

from scipy.stats import uniform

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from tqdm import tqdm

num_total_samples = int(1e7)

num_batches = 250

num_batch_samples = np.logspace(np.log10(1e2), np.log10(num_total_samples), num_batches, dtype=int)

X_samples = uniform(0,1).rvs(num_total_samples)

Y_samples = uniform(0,1).rvs(num_total_samples)

for batch_idx, num_samples in tqdm(enumerate(num_batch_samples)):

X_batch = X_samples[:num_samples]

Y_batch = Y_samples[:num_samples]

good_sample_indices = np.where(np.sqrt(X_batch**2+Y_batch**2)<=1,)[0]

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(5, 5), dpi=80)

ax.scatter(X_batch, Y_batch, s=0.1, label="outside")

ax.scatter(X_batch[good_sample_indices], Y_batch[good_sample_indices], s=0.1, c="tab:orange", )

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.set_xlabel("X")

ax.set_ylabel("Y")

ax.set_title(r"$\pi \approx$"+f"{4*len(X_batch[good_sample_indices])/num_samples:.4g}, N={num_samples}")

plt.savefig(f"Pi_Example_GIF_Pics/{batch_idx}.png")

plt.close()

from PIL import Image

import os

png_dir = "Pi_Example_GIF_Pics"

# Output GIF file

output_gif = "estimating_pi.gif"

# Get a sorted list of PNG files

png_files = sorted([f for f in os.listdir(png_dir) if f.endswith(".png")], key=lambda x: int(x.split('.')[0]))

# Create a list of images

images = [Image.open(os.path.join(png_dir, f)) for f in png_files]

# Save as a GIF

images[0].save(

output_gif,

save_all=True,

append_images=images[1:],

duration=200, # Duration of each frame in milliseconds

loop=0 # Loop forever; set to `1` for playing once

)

This brings up an important point within Monte Carlo methods: they are often easy to conceptualise and implement, but they are also sometimes shit. The GIF above goes to 10,000,000 (10 million) (1 with 7 zeroes behind it) (ten thousand thousand) (ten to the power of 7) (roughly the population of Greece) (a lot of) samples, and it can’t even get \(\pi\) to a few decimal places. It is important to try out various approaches to difficult problems, and trying not to make the solution difficult as well.

Example 3: Inverse Transform Sampling

I covered Inverse Transform sampling in another post, but a quick summary of the method is:

- you generate random samples uniformly distributed between 0 and 1;

- these feed into a target probability distribution’s inverse cumulative distribution.

This generates representative samples of your target distribution.

Example 4: Accept-Reject Sampling

I covered Rejection Sampling in another post, but a quick summary is that it is a method where you:

- sample values in a target probability distribution’s sample space either using a proposal distribution such as the uniform distribution over the whole space or with a more constrained distribution (e.g. a gaussian centred about the mode of your target distribution);

- generate an equal number of uniformly distributed samples scaled by the probability of those samples under the proposal distribution and some scalar multiple to ensure that the highest value is larger;

- reject any samples that have values larger heights than the target probability density for the sample.

This generates representative samples of your target distribution.

Example 5: Monte Carlo integration

Monte Carlo integration uses the trick that if you have a probability density of \(x\), \(p(x)\), and any reasonable function \(f(x)\), then

\[\begin{align} \int f(x)p(x) dx \approx \frac{1}{N_s} \sum_{k=1}^{N_s} f(x_k), \end{align}\]where \(x_k\) \(\sim\) \(p(x)\) (\(N_s\) representative samples of \(x\) under \(p(x)\)). Intuitively, this can be understood as the left-hand-side is the average of \(f(x)\) weighted by \(p(x)\); so if we generate a bunch of samples from \(p(x)\) and then take the average of \(f(x)\) (the right-hand-side), this should be approximate to the integral.

This means that if you have an integral that involves a probability density that is difficult or fundamentally impossible to analytically derive, but you can sample the probability density, then you can create an estimate of the integral using samples! This also combats the curse of dimensionality that would occur with other methods. If you were to try and do the integral numerically, such as using Simpson’s rule, then the number of required grid points to evaluate at exponentially grows with the number of dimensions. e.g. If you just have ten values per dimension that you wish to look at for the integral and have a 12-dimensional integral, this corresponds to (assuming 64bit precision) roughly 64 Tb of memory…and I don’t know many integrals where you just need to evaluate 10 values per dimension…

Things to remember

The main takeaway from this post is that MCMC is the combination of two concepts in statistics. You generate samples using a Markov chain to get some sort of statistical result (emblematic of Monte Carlo methods), typically in the form of samples representative of a target distribution. However, true samples of the distributions shown are independent of each other, as the value of one does not impact the value of another, but this is not the case for samples in a Markov Chain. In fact, by its very construction, the samples are correlated with each other15. Recognising whether this may be an issue in your analysis will require diagnostics that I will try to detail next.

Next Steps

In my next post, we’ll dive into diagnostics for MCMC chains. We’ll cover:

- Tools to assess convergence (e.g., trace plots, Gelman-Rubin statistic).

- Effective sample size (ESS), and why this all matters.

For legal reasons, not really ↩

I know this is a bit vague, but this in part because of the wide range of outputs you can get from Monte Carlo methods. Plus, I’ll detail some concrete examples below. ↩

I do love that this relatively abstract concept, which has broad implications not only for day-to-day life but for advanced statistical methods and many concepts in the natural sciences, is taught in the base maths curriculum in Victoria but not the more advanced maths curricula?? Good job VCAA. ↩

Most Markov chain examples start with two total states, so the transition matrix is 2x2. But I want to make clear that if there are \(n\) possible states in the discrete space of states then the transition matrix is \(n \times n\) describing how each state transitions to every other state. ↩

Cars can’t be in two places at once, presuming they’re in one piece and we’re not doing quantum mechanics here. ↩

I prefer the no subscript version as it means that I have to type less. ↩

discrete/continuous. The example I give is a discrete case and we’ll get to continuous cases later ↩

The dependence only on the immediate precessor is sometimes referred to as the “Markov Assumption” or “Markov Property”. ↩

Detailed balance is not only a concept in Markov chains, it also relates to many physical phenomena (e.g. Einstein and his description of radiation emission and absorption), but I discuss it as such for brevity. ↩

I’m using relatively non-standard notation here, but I want to be consistent with the above rental car example. ↩

And you believe me for now ↩

You better appreciate this math, had to rewrite this thing 6 times … ↩

Reminder, the Metropolis algorithm is the special case of the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm when the proposal distribution \(q\) is symmetric, \(q(s_i\mid s_j)=q(s_j\mid s_i)\) ↩

Fun fact, the method’s name was inspired by one the main developers Stanislaw Ulam’s uncle who would borrow money from his relatives to go gamble in Monte Carlo… ↩

To be exact they are autocorrelated ↩